Where are the heroes for Kind Boys?

- Nov 4, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 5, 2020

Now that my kids can finally read full-length chapter books, I'm discovering that the lack of positive role-models for non-stereotypical boys extends way beyond the early years. The shelves in my local bookshop are stacked with tween-girl sleuths and pirates and escapee orphans and athletes, all defying the stereotypes as well as the odds. But you'll struggle to find a book about a straight tween boy whose triumph doesn't lean heavily on traditionally masculine qualities: fear suppression, physical prowess, risk-taking, dominance, stoicism. Even beloved modern characters like Harry Potter follow the formula: The boy wizard is a surly, book-shy, athletically gifted "chosen one", who shines in solo combat and is given to bursts of anger. A superhero with a wand.

Lisa Selin Davis, author of the new book Tomboy: the surprising history and future of girls who dare to be different, notes this gap in a recent article. "We recognized a long time ago what kinds of images we needed to present to girls to free them from the binds of stereotypes," she writes. "Tomboys were the heroines of lots of 19th century literature [...] But in many of those tomboy books, the male best friend is a “sissy” — there’s no positive masculine version of tomboy". Selin Davis argues that not only is this is a problem for boys who don't conform (or even aspire) to the bravado stereotype. It's a problem for girls and women, too. Because when we persist in seeing things like emotional intelligence, thoughtfulness and sensitivity as female qualities, we are assigning them lower cultural value. This makes it less likely that boys will cultivate them as they grow up—leaving all that emotional work to women (often unrecognised and unpaid.)

The publishing industry is taking stakes in the masculinity debate. So far, it has responded mainly with books aimed at adults (like Rebecca Asher's Man Up: How Do Boys Become Better Men and Robert Webb's memoir, How Not To Be A Boy). But a few offerings for children themselves have begun to appear.

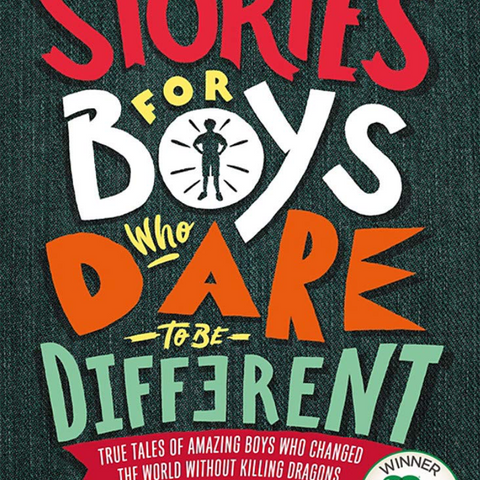

There's the best-selling non-fiction compendium Stories For Boys Who Dare To Be Different, riffing on the wildly popular Goodnight Stories For Rebel Girls formula. There's the charming manifesto Declaration of The Rights of Boys/Girls (one book that reads from both ends, asserting the rights of boys to be "clean, sweet-smelling, stylish and well-behaved" as well as the rights of girls to be "untidy, scruffy, covered in scratches and hyper"). And there are read-aloud picture-books that celebrate 'un-boy-like' pursuits like intense best-friendship (Jerome By Heart), and decorative crafts (Made by Raffi).

There is still a glaring gap though.

The gap is fiction. Especially pre-adolescent chapter-books, the kind that draw early readers in and stokes their first under-the-covers torch-lit sessions. That's a shame, because the fiction books we encounter between the ages of 6 and 12 have a special power:

We remember them. Think back to the books you cherish from childhood: Aren't many of them from this golden moment when you had a foot each in the worlds of fantasy and reality?

They shape our moral and narrative imagination. We get our core ideas of inner struggle and ethical behaviour from these books, as Phillip Pullman described beautifully in Daemon Voices.

They reach us at an age when our ideas of gender are pliable. Studies like this one argue that 'middle childhood' is the timeframe "when children’s conceptualization of gender norms increases in flexibility, making it possible for girls to ‘blur’ the boundaries between boys and girls." Many girls respond to this cognitive leap by ditching the pink frills and playing with a wider palette of gender expression: the Tomboy phase. Boys simply don't have that wider palette available to them.

What would it look like, this wider palette for boys? Well, it would probably still follow the universal 'hero's quest' formula, but perhaps with a different kinds of quest and a different set of superpowers—an emotional skill-set as powerful as any patronus. As Selin Davis says, "The problem is that so much good stuff is marked “feminine”: kindness, empathy, nurture, an interest in and skill at maintaining relationships." And feminine, in our society, means lower status. But if we could develop new heroic narratives around boys who display these qualities, we could change that—to the benefit of boys and girls alike.

You might be struggling to conjure a boy-hero who isn't a dare-devil, a stoic silent type or some kind of Chosen One. I certainly do. So, what if we look to the real world for our models. They are out there, the boys whose triumph has been to care deeply. We could do worse than start with real Kind Boys.

Have you noticed this gap? Have you stumbled across any amazing hidden treasure books with Kind Boy heroes? Let me know in the comments.